A Day in the Life of Govanhill Library

Earlier this year Glasgow City Council announced to much dismay that it would be slashing The Mitchell Library’s opening hours due to budget constraints. Closer to home, community reporter Flora Zajicek spent time in our local library to understand how the space was used by different people and what impact it has on people’s health and wellbeing.

By Flora Zajicek || Photos by Iain McLellan

Recently, I was angered to read a tweet from a politician suggesting we might save money if we cut funding for ‘useless’ public services like libraries. Research has shown just how beneficial libraries can be for health and wellbeing. So at a time of stark health inequalities, I wanted to hear just how important the Govanhill Library is to the wellbeing of the local community.

Established in 1906, Govanhill Library was one of many purpose-built spaces erected in the years following the Public Library Act of 1850. It was a time of urbanisation and these grand buildings were a dedicated, free space for the pursuit of knowledge for all. I like to imagine a strict librarian shushing whispering schoolchildren and prodding people with her cane towards self-betterment.

Original floor plan for Govanhill library

After long, gruelling days of work, people could entertain themselves and their families with borrowed books from this new temple of stories. Originally, there were skylights in the reading rooms, separate rooms for boys, girls and ‘ladies’, as well as stands of broadsheet newspapers and a central area in the middle of it all, simply marked ‘public space’. The library was – and still is – crowned with a big sandstone dome and two enormous figures of women reading to children. There are high ceilings (though unfortunately the skylights have been covered over) and neoclassical columns; it still bears the traces of an ambitious, socially-minded ideology, but times have changed.

“I used to come here as a boy after swimming in the baths,” Michael tells me. Now working as a support worker, he grew up on Victoria Road tells me. “It used to close at about six back then, 40 years ago, and I’d come here and read books or take out books. It was definitely something I enjoyed, I loved books. I could come alone, as long as I got home in time for tea – it was a safe place that you could come to on the long winter nights.”

Like Michael, you might associate books with relaxing, escaping, and gallivanting into other worlds. In fact, the benefits of reading have even been shown to have a positive impact on our health, both mentally and physically. One UK-wide survey revealed people who read for 30 minutes a week are 18 percent more likely to report relatively high self-esteem and greater life satisfaction, and non-readers are 28 percent more likely to report feelings of depression. Other research has found that reading for just six minutes a day can reduce stress levels by 68 percent. It’s not just through access to books, however, that this library can benefit wellbeing.

Now, Michael works with homeless people in the area and uses the sofas in the library as a quiet space to come and decompress or catch up on emails between seeing the people he supports. He tells me that lots of the folk he works with use the library for its computers and the books in foreign languages like Urdu: “It’s a really calm, positive environment; a wee oasis in amongst all the noise of life.”

Govanhill Library 1907 | Source: Glasgow City Archives

The Health on a Shelf report ‘commissioned by the Scottish Library and Information Council in 2019 to examine the health and wellbeing services available in Scotland's public libraries’ showed just how crucial libraries are to improving the health literacy, and consequently, health outcomes, of people in Scotland. Librarian, Alison Nicol, tells me that they have books about medical conditions, books for people with dyslexia, books in large print and audio books you can get for free online or in the library. She also highlighted that all the Glasgow libraries are connected, so if they don’t have the book you’re looking for, they can order it from another library or buy it in for you.

As I spend time in the library, it’s obvious that many people are coming here for practical things; printer use, free wifi, or for the computers. In Glasgow, 65 percent of households living in the city's social rented housing sector do not use a broadband connection in their home, and nineteen percent of Scottish people have no digital skills. Across Scotland, there are big differences in terms of internet access between the most and least deprived areas. And there’s a proven link between people who are digitally excluded and higher health inequalities. Libraries combat this through the provision of wifi and computers as well as digital literacy training programs.

The librarians I spoke to told me that increasingly they field requests for help with visa applications, pensions, or advice on things like winter fuel payments. Alison explains that after a steady decline in public services during the austerity years, libraries are one of the few remaining spaces where people can come to and speak to someone face to face for help: “As much as for the practical things, people rely on the library for warmth and for a chat – it plays a big role in reducing social isolation.” The library has a book club on Fridays and they’re happy to support people creating new book clubs by providing multiple copies of books and offering space in the library to meet.

Margaret Russell is leafing through a magazine when I meet her: “I used to think of libraries as quite austere places,” she says. “I grew up in north London and you really couldn’t say a word. Here it’s not like that.” She’s lived in Govanhill since 2015 and comes to the library to take out books and magazines. With no computer at home she also comes to use these. “I live on my own and am prone to depression but coming here and seeing familiar faces is a real mood-lifter. It’s nice to know there’s a place I can come and just chill out and that’s okay.”

One of the two childminders I spoke to was sitting in a big comfy chair knitting with a baby fast asleep in a pram next to them: “This is a quiet, warm, free, sheltered space that I come to. It’s not transactional, you don’t have to buy anything like in a cafe.” They tell me about the Bookbug sessions the library runs on Saturdays with stories and songs for young children and the great range of kids books.

The Bookbug scheme is an attempt to ensure that every child in Scotland has access to books in their early years. Research by the Literacy Trust showed a correlation between lower literacy rates and poorer health outcomes. In Scotland, every child can get four free bags of books and other age-appropriate resources; as babies, toddlers, three and five year olds. One of the childminders says: “All the families I work with use it pretty regularly and I want more people to use it so they don’t go away, it almost seems too good to be true in this day and age, I really want them to keep going.”

Michael has headed out to see his next client, and three teenage boys have taken his place on the sofas. “We chill here after school because there’s no internet at home, here we can use the free wifi and sometimes we watch YouTube on the computers.” One of the boys tells me he sometimes flicks through the books to learn English. When I tell them they can actually borrow these books and take them home for free, all three are at first incredulous “with no money?” then excited “can we get a card now?”.

I was left wondering where else these boys might go if the library didn’t exist, and also about the future roles of libraries for new generations. They are growing up in an age of vast technological difference from their counterparts of 120 years ago but still face the challenges of poverty and harsh winters.

Communities Services Supervisor, Karyl Seguin, tells me that they’ve seen large groups of young people coming to the library after school. She tells me sometimes they get noisy and that recently they have had the police come in to show a presence. It strikes me as a broken system when the only port of call is this. Where are the steps in between? Librarian, Alison, says: “They’re not bad kids, it’s just when there’s bad weather or it’s cold and dark, they’re bored. They don’t have anywhere else to go.” They have since partnered up with Govanhill Community Renewal who have arranged for various staff members, including a youth worker, to come and offer things like Duke of Edinburgh sessions to these young people.

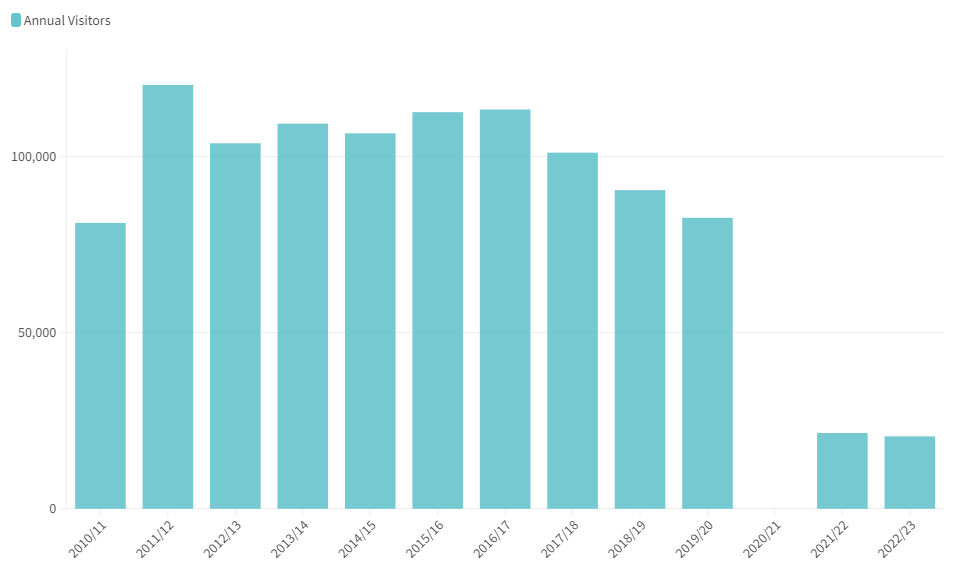

Govanhill Library annual visitors 2010/11-2022/23

Last year after a parliamentary question, it was revealed that since 2009, 83 libraries have closed down across Scotland. In the same period, funding for public libraries was reduced by 30 percent. It’s clear that libraries are one of the few remaining public services left to fight the fires caused by years of chronic underfunding in the public sector and they are stretched. Yet the return to libraries and cranking back up of their previous activities has been sluggish since Covid-19. Govanhill Library didn’t open after the pandemic until March 2021 and then was closed for 14 weeks for an upgrade in 2022. The usership now is still less than a quarter of what it was in the four years preceding the pandemic.

Despite a promise from Glasgow Life that from the Scottish Government Public Library Covid Recovery Fund grant, over £22,000 would go towards a home library service, the Govanhill library is still not offering this at the moment due to a lack of volunteers. Recruitment for volunteers is now underway and once it’s up and running, library users who can’t make it to the library in person will be able once again to have books relevant to their interests delivered to their door.

The stained glass window inside

Wandering around the space and lifting my eyes up above shelf level I notice a series of bright, stained glass windows ribboning around the edge of two walls in the central room. These were made in 2015 for the Diversity Windows project. Each one was created by a different community group from Govanhill. “I remember when they first came”, says Margaret. “This area has a colourful history, and now all the community is represented through them. It’s a bit like going to a church with stained glass windows. This library is the hub of the Govanhill community.”

Looking more closely at the colourful panes of glass, it’s impossible to ignore just how many different people this library is here to serve. I think again about that original plan with ‘public space’ labelled in the middle. Whether you come for the quiet, the warmth, the books or the printer, this is a dedicated space for you to simply be. Libraries are one pane of colourful glass in the stained glass window that makes up the wellbeing of our community. They diffuse beautiful colour onto our neighbourhood but form part of a tapestry of light when blended with other public services that keep us well.